Review

-

Tagore play gets a tribal flavour

In a Santhali adaptation of ‘Raktakarabi’, Partha Gupta’s ‘Ara Baha’ uses choreography, acting and visual motifs to communicateIncessant rains had forced the Santhal members of the Birbhum Blossom Theatre to leave their usual performance site in Dwaronda village. The clay stage that they had built, with palm frond wings and backdrop, soaked in the showers, just like their huts and would have to be painstakingly repaired later on.

But for the moment the team concentrated only on the show. Even the stage at Srijani in Sriniketan, rather inadequate and disagreeable, couldn’t curb their enthusiasm. Artistes of our country are largely agreeable. And once the performance began, even the audience (many of them academics and urban theatre buffs) forgot to complain about the mosquito-infested flat viewing area and dirty plastic chairs.

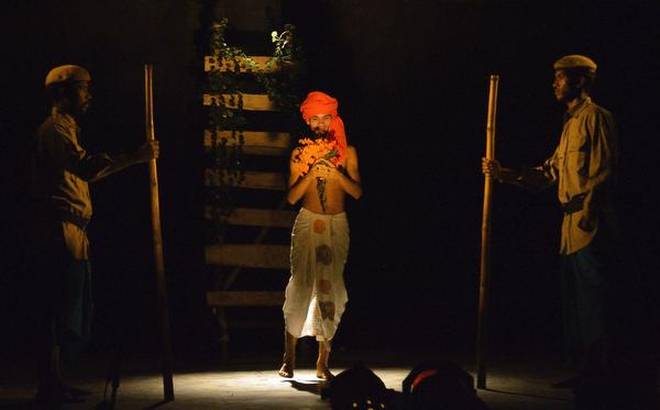

The play began with the lights rolling off a vertical structure, perhaps representing a daunting tree or cliff face. At the very top was a bunch of flaming red flowers. On the ground armed guards kept vigil. The lights increased as a youngster in white descended the structure with the flowers in his hand. His smiling visage made us momentarily forget the guards lurking in the shadows thus increasing the impact of their brutal attack. The unrelenting oppressive darkness of Yakshapuri took over.

Expectations ran high as this unique Santhali adaptation of Tagore's ‘Raktakarabi’ unfolded. The sight of raktakarabi or red oleander blossoms crushed by metal junk in Shillong 1924 had inspired Tagore to write this play that conjures up a vision of an arid mechanised world where man’s greed and power loots the earth of gold yet man is himself reduced to a slave with a number instead of a name.

Symbolism of red colour

In 2017, director Partha Gupta, has given up the exotic feel of raktakarabis to use the title ‘Ara Baha,’ which just means any red flower. The emphasis is on the red colour with all its associations of life giving blood, of love, spontaneous passion, even revolt. The title also calls to mind the tenderness, beauty and fragility of live petals.

Partha (38) is from Birbhum and has lived close to the Santhal villages for many years imbibing their culture, their music, dance and rituals some of which he has incorporated in a book. He studied drama at Rabindra Bharati University, Kolkata, and spent time observing master theatre director Ratan Thiyam working with his group Chorus Repertory Theatre in Manipur.

All this prepared him to work with a tribal community that knew nothing of theatre or Tagore. Apart from the difficulty of translating Tagore’s lines and communicating the complexities to the villagers of Dwaronda, Partha felt it was text-heavy. “So much dialogue is no longer needed to communicate Tagore's work,” he says. So he did away with most of the dialogue and used choreography, physical acting and visual motifs to communicate the essence of the play. Interestingly, the play has survived.

The few lines of Santhali dialogue, their music and dance expressed the angst of the soul. The fact that this was happening close to Tagore’s Visva Bharati seemed significant. If the Bohurupee’s faithful production of Tagore’s text directed by Sambhu Mitra was a landmark, this presentation by the marginalised Santhals, who worked in the fields and were largely illiterate, seemed closer to the bard’s dream of his songs uniting with life.

With texts widely read like Shakespeare and Tagore, the presentation can afford to be suggestive. So it is not difficult to identify the Yakshapuri with its terrible Raja who remains hidden to keep up his image of omnipotence and Nandini decked in red flowers that symbolise her love for Ranjan and the promise of life and joy.

The first scene of ‘Ara Baha’ easily substitutes the long interaction in which Nandini worries that Kishore will get into trouble for skipping work at the mines to go looking for the raktakarabi and Kishore says that for her, he would happily lay down his life.

To Partha the play was the bard’s expression of personal crisis, a terrible internal tussle, not some international political statement. Raja and Ranjan are parallel identities Nandini loves them both and Nandini is empathetic to a number of lesser characters who like reverberations of both Ranjan and Raja, are charmed by her.

Ranjan, never shown on stage by Tagore, makes a brief appearance here as a young man playing the banam, a traditional Santhal string instrument. When later Nandini appears cradling the banam like Ranjan’s corpse, or a child, the message that a musical instrument can begin to play again at any moment is beautifully suggested.

In the Santhali rendition, Nandini is seen transforming or rather opening out like a butterfly from a chrysalis. The leaf woven Pekhe (used by rural women to shelter from rain while working in the fields) is used here as the covering that Nandini takes off. The teacher muses over the shed Pekhe as if to understand and analyse Nandini better. A traditional mask dance Banshai is used to convey the sense of threat and traditional Santhali songs are used instead of Rabindra Sangeet. “I don't compose anything, I apply,” said Partha.

Not all his efforts work, however. There is confusion in parts and some introductions like the Professor wearing gloves because he can’t touch Nandini and the red dais to the triumph of life over death and violence seem a little out of place.

Durga Baski (Nandini), and Suriya Hembrem (Kishore), are in class XII of a local school. They have been doing theatre since 2013 and show no signs of backing out. While the men play truant at times, the women, who dominate in the community, are regular at rehearsals and are professional in their outlook. Partha pays them on a daily basis and arranges for snacks. One waits for the day when his efforts will prompt the Santhals to tell their own stories on stage.

To Partha the play was the bard’s expression of personal crisis, a terrible internal tussle, not some international political statement